Part four of my seemingly endless review of Bryan Caplan’s The Case Against Education. Parts one, two, and three.

If you follow me on Twitter, you know I get very, very irritated whenever Pew releases a new poll about “Americans” and their increasingly positive feelings about immigrants, because they aren’t surveying Americans, but adults who live in America.

Cite: Same source Caplan used |

As Mark Hugo Lopez of Pew confirmed to me, back in 2016, “We asked our immigrations of all U. S. adults, including non-citizens.” They don’t disaggregate the responses by citizenship or immigrant status. In fact, they even ask all the adults if they are Republicans or Democrats when immigrants can’t be registered voters. This is just spectacularly dishonest and I get mad every time I write about it, but I mention it here for another reason:

“In 2003, the United States Department of Education gave about 18,000 randomly selected Americans the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL).”–Bryan Caplan, The Case Against Education, page 41. (emphasis mine)

NAAL did not survey American adults, but rather adults living in America. 13% of those surveyed were raised in a language other than English and are very probably immigrants. Another six were raised in households where the parents were native speakers of another language, and we can probably assume most were children of immigrants.

Here’s how Caplan characterizes the overall results:

|

Only modest majorities are Intermediate or Proficient in the prose and document categories. Under half are Intermediate or Proficient in the quantitative category.

…

Eighty-six percent of Americans exceed “Below Basic” for prose; 88% exceed “Below Basic for documents; 78% exceed “Below Basic” for quantitative. For each of these categories, 13% are actually “proficient”. Bryan Caplan, The Case Against Education, page 41. (emphasis mine)

Please note the use of “Americans”. You can decide if he’s lying or careless while I continue.

What does the data look like if you isolate native English speakers and compare them to non-native speakers?

Eliminating non-native speakers reduces the “Below Basic” prose scores by 35%, while “Intermediate” readers increase by 11%. “Proficient” readers increases by 15%. The document scores see less dramatic changes, but 1 in 4 of every “Below Basic” scores disappear.

You can rewrite Caplan’s text above:

Over three fifths of Americans are Intermediate or Proficient in the prose and document categories. [Note: quant scores weren’t made available for disaggregation.]

…

Ninety one percent of Americans exceed “Below Basic” for prose; 91% exceed “Below Basic for documents…

Not nearly as horrible, are they?

Of course, Caplan also wants to convince the reader that education has little to do with human capital but is primarily signaling. What better way to achieve this than by showing how little education improves the public’s reading scores?

|

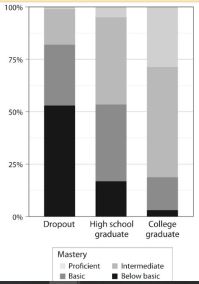

“While today’s dropouts spend at least nine years in school, over half remain functionally illiterate and innumerate. Over half of high school graduates have less than the minimum skills [intermediate] one would naively expect them to.” The Case Against Education (page 43)

This graph doesn’t match up exactly to the report (he cites pages 36-37), because he averages the three reading test averages and then selects only the results for the categories High School Dropouts, High School Graduates, and College Grads. So the data above is only for 53% of the surveyed population and averages prose, document, and quantitative.

So Caplan is, deliberately or carelessly, due to sloppiness or dishonesty, inviting the reader to assume that all those tested are reading their native language. He constantly uses the term “Americans” when over 1 in 10 was almost certain born elsewhere and probably schooled elsewhere. He also never once considers different populations or suggests that we should have anything other than identical expectations for every segment of American society (more on that in another article).

Happily, each NAAL survey generates a lot of research. Six years after the NAAL, another report dug deep into the non-English speaking results: Overcoming the Language Barrier: The Literacy of Non-Native-English-Speaking Adults. To confuse things, the researchers use the words “High Prose Literacy” and “Low Prose Literacy”, combining the four categories two by two. But this new report provided score averages on both language and education levels, while the one Caplan used only provided scores for language or education levels. (From here on in, all data is Prose only)

These graphs (I assume I could have combined them into one Excel chart but couldn’t figure out how), combines the data from the overall NAAL report and the non-English speaking drill-down. The chart on the left is Low Literacy Prose results (Below Basic and Basic) broken down first by language and then by education. The chart on the right is High Literacy Prose results (Intermediate and Proficient) in the same way.

So right away, it’s obvious that native English speakers are providing almost all the high literacy results, while non-native speakers are contributing an enormous chunk of the low literacy results. Roughly 20% of the tested population, the non-native English speakers, is responsible for a third of the low literacy scores. Nearly 7% of all responders were non-native speaking dropouts, comprising the overwhelming portion of low-literacy non-native speakers. Most of the latter group probably didn’t ever attend American schools, although that’s not provided by the data.

Also of interest: 20% of the the high literacy (intermediate and proficient categories) native English speakers had no more than a high school diploma, while 27% went on to some college and an equal amount went on to graduate and post graduate degrees.

The other half of native English speakers who stopped their education after high school–scored Basic or Below Basic, comprising 42% of all the low literacy scores for that group. I was interested to see that high school graduation numbers aren’t much affected by the switch to native English speakers, suggesting that immigrants are overwhelmingly high school dropouts, followed to a much lesser degree by college graduates. While their percentage contribution to low and high literacy populations vary, the actual number of high school graduates in each group is about the same (more on that later). Caplan finds it appalling that high school graduates who didn’t go on to higher education are roughly split between four categories. I’m actually encouraged at how many high school graduates are in the top half of the literacy categories.

Ironically, this data slice also clearly shows the flaws in the American system much more clearly than the rather simplistic argument Caplan is making. As I mentioned in the last chapter on college graduate quality, colleges are increasingly accepting people who have not demonstrated college readiness. Almost certainly, some non-English speakers would have both college degrees and poor prose skills. But 7% of native speakers with low literacy rates are college graduates. In absolute terms, nearly 9% of the low literacy population attended at least some college.

Here’s one last take on the data that I used to check my compilation. The orange line is the percentage of each category in the overall Kutner report (that Caplan used). You can see that it’s off slightly, which I’d expect, but mostly in line.

Each column is green pattern, blue pattern, solid green, solid blue. The blues are native English speakers, the greens non-native English speakers. The patterns are low literacy, the solids are high literacy.

This graph shows how much of each category is dragged down by non-native English speakers with low literacy–anywhere from 6 to 39 percent. Also clear is that non-native English speakers with high proficiency have very little impact on the overall results.

In particularly, non-native English speakers with low literacy are simply overwhelming the high school dropout category, punching far above their weight. Also observe how clearly this graph that substantial numbers of high literacy readers are stopping education in high school while other low literacy readers are moving onto college and even graduating. Clearly, we aren’t doing our best to identify and educate our strongest students. This might explain why the returns to education are less compelling than they might be, which is again linked to college quality control, not failures in the act of teaching.

********************************************************************

Non-native English speakers may have gone to American schools, and there are some Indian, English, and Australian speakers in the native English results. But the second group would be overwhelmingly found in the college graduate categories. And if we are to concede that American schools don’t always educate non-native speakers as well as native speakers, we should also grant that no other country in the world expects its schools to educate millions of non-native speakers, much less be judged on the results. So I think it’s quite fair that if we are to consider prose reading skills a proxy for the quality of American education that we consider how the schools educate the people they were originally intended for.

I can’t for the life of me imagine how Caplan was able to get away with including immigrants in his NAAL results. It’s the same utterly dishonest bias that permeates the Pew data, but Caplan’s an academic, this book was published by Princeton Academic Press, has been reviewed by a zillion reputable people, and he is either dishonest or incompetent regarding a key element of his case against American schools.

But that’s not all, as anyone familiar with Caplan understands. Caplan is a libertarian and the leader of the open borders fringe. He argues that America and other countries’ welfare states are an incentive and rationale to restrict immigration, and sees K-12 education as an “indefensible universal program”.

So Caplan wants to end what he considers wasteful public education.He also wants millions of the world’s poor to immigrate to America, and believes this idea would be less controversial if we weren’t obligated to provide welfare and education to the immigrants and the subsequent generations. Hence he argues to end public education as a means to his ends of open borders.

It’s a bit odd, isn’t it, that he just somehow doesn’t notice that he’s rigging his case against American education by including the scores caused by very immigration policy he wants to expand?

|

As Kutner report makes clear, pulling out non-native speakers demonstrates that native English speakers improved their scores over the last decade. Those with mixed language backgrounds improved as well. Meanwhile, native Spanish speaker performance plummeted from its already low 1993 baseline, while the tiny Asian population improved either because the source countries changed or perhaps more Asian Americans grew up to improve the scores.

Incidentally, the other knowledge tests Caplan uses to demonstrate our useless education system are similarly biased. He uses the General Social Survey but doesn’t restrict the results to citizens. The American National Election Survey limits its sample to citizens, at least, but that would still include many people who hadn’t been educated in American schools.

I would like to believe the best of Caplan and that he was just careless or sloppy. But I keep bumping into the fact that Caplan couldn’t disaggregate without explaining why. Explaining that non-native English speakers skew the results would alert readers to the fact that immigrants were so numerous that they were skewing our educational results, making the country appear less capable. He can’t alert the reader to the cataclysmic results that our immigration policy is inflicting on our national education profile because he wants millions more immigrants to further obliterate our educational profile.

All of the bad data shows up in Chapter 3, where Caplan uses it as a foundation for his argument that public education is a waste of time, that Americans’ utter failure to supports his argument that education credentials are all signaling. It’s just one chapter, but it’s the foundation of all the subsequent ones, as he offers it as a given that Americans are stupid useless gits who can’t remember everything they’re taught, which is why education is primarily signaling, and why we should gut our public support for all education.

Once you take out immigrants, American education looks pretty good, and our challenges are clear. We need to seek to improve our educational outcomes for high school, convince our high school dropouts to stay in school (purely for signaling) and we need better paying jobs and more affordable housing to convince them that there are good futures out there for hard work.

Immigration doesn’t help us achieve either of those goals. I understand Caplan disagrees, but he shouldn’t juke his stats. He especially shouldn’t hide the fact that the very immigration changes he argues for leads to an educational profile he finds so ridiculously awful that he considers it evidence we should stop bothering to educate Americans.

(Final note: I have spent a month trying to get this data right and be sure I didn’t make a mistake. I might have anyway. One thing I know, though: I spent more time trying to make sure the NAAL data reflected something closer to American achievement than Caplan did. And I wanted this sucker done. I’m so exhausted of thinking about it. If something’s not clear, please email me or mention it in the comments.)