Back in February, I observed that Direct Instruction hadn’t failed because of teacher disdain, as Robert Pondiscio charged, but because educational leadership from superintendents on up through US senators had not only refused to support the program, but in some cases actively and systemically ripped out implementations that seemed to be successful. As I said at the time, I considered it a real mystery.

So I dug deep into Zig Engelmann’s book, Teaching Needy Kids in Our Backwards System looking for an example of a success story I could independently verify. He goes on at some length about both San Diego and Baltimore schools, but not in any way I could pin down DI vs. Non-DI. Quite often Engelmann would cite a newspaper article as evidence.

The Ventura County Star carried an article on March 15, 2003, titled “Effective Reading Program Must Go”, which indicated that the only school in Ventura County and one of 109 in the state to receive a citation for achieving exemplary progress was forced to drop their [DI] program.

No mention of the school. Or the superintendent. Or the degree to which test scores increased. One gets the distinct impression that Zig….well, read about it in the paper. He uses virtually identical wording in this Edweek article. California keeps detailed, easily searchable records; with the name of the school, the specifics of the decision could be confirmed.

The exception is Lewis Lemon.

But then, as happened consistently through the decades, a new superintendent came in and demanded Lewis Lemon abandon Direct Instruction and adopt “balanced literacy”. The principal, Tiffany Parker, flatly refused. She was accused of cheating, so the students were tested again. They passed the new test. The district actually had to give back Reading First federal funds because they dropped DI. Apparently, the district blamed the principal for informing the feds that the district was no longer using the program, and Parker was demoted. She sued, and settled. If you google this, you’ll find a New York Times article, a New York Sun article, this Heartland article, and references to many Rockford Register Star articles by Carrie Watters, who from what I can tell now works at an Arizona paper. The Rockford Register Star archive goes back before 2003, and has other articles by Carrie Watters, but contains none of the many stories Watters did on the Lewis Lemon controversy. Even Joanne Jacobs’ blog entry on Rockford, “They Messed with Success” has disappeared, which had me really freaked until I learned she was had temporarily moved her archives.

The story made national headlines when the superintendent decided, in 2005, to force Lewis Lemon off of DI into “balanced literacy”, while the strong student performance of 2003 only got covered locally. The New York Times piece went into a bit more depth, mentioning that the fifth graders didn’t do as well. Also, the reports weren’t always specific. Was it math or reading? Or both? So I went digging for data.

If contemporaneous reports are scarce, the contemporaneous data survives. Illinois test scores comparing Lewis Lemon performance to the district and state by race are all online. Here they are, and please check my results:

2001–the year they implemented DI

2002

2003

2004

2005–the year they were forced to discontinue DI

2006

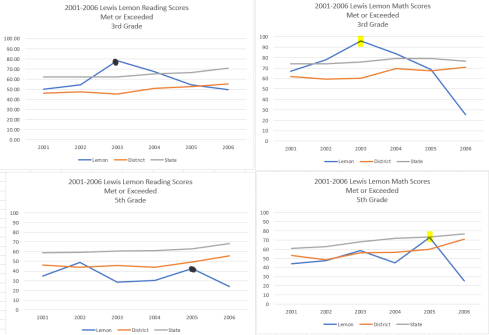

So now I’m going to go all graph heavy, like Spotted Toad. First up: the top level comparison of Lewis Lemon scores to the district and state level for both 3rd and 5th grade (reading down).

Note the big ol’ spike in 2003. Lewis Lemon 3rd graders had far more students meet or exceed standards than the district or state averages in that year. But then, third graders at Lewis Lemon outscored the district average every year both before and after DI was implemented in Notice, too, that the fifth grade scores aren’t nearly as impressive, but that both math and English show a spike in 2005, which is the year the third graders of 2003 would have been in fifth grade. Then again, fifth graders had much better reading scores in 2002 than in any time after DI implementation.

Lewis Lemon officials blame the lower fifth grade reading scores on a less than perfect implementation, and students who were further behind. On the surface, this seems unlikely, given the high scores in 2002. But there may be other causes.

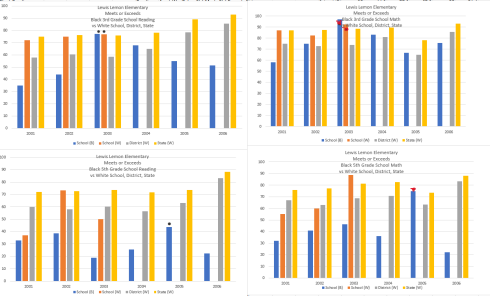

So I disaggregated, first by race. Here are black and white 3rd grade reading score scores compared at the school, district, and state level, broken down by achievement category.

Up first, 3rd grade blacks:

Now remember, this is Lemon Lewis black students compared to other black students only (not the entire population). Blue is Lemon Lewis, and the more blue to the right of each graph, the better Lewis Lemon is doing. 2003 is the year of the Big Score. The blue clearly moves to the right from 2002 to 2003, and stays there for two years. Then it shifts back.In 2003, black students at Lewis Lemon met or exceeded standards at 3 to 4 times the numbers that district or state black students did.

Third grade reading, white students.

So this is interesting in a couple ways. First, it’s clear that in the pivotal year of 2003, white performance actually declined slightly. Fewer students failed to meet standards, but fewer students exceeded them. Not a lot. But there’s no tremendous spike in white student performance in 2003.

And then, something that has gone completely unmentioned: the white student population collapsed to below testing levels immediately after 2003. This explains some of the falloff of the graph above–if whites comprised a decent chunk of the high scores, then their disappearance would impact the overall “meets or exceeds”.

It’s not clear to me whether the DI implementation was reading only, or reading and math. The news accounts all focus on reading, but more than one account mentions improved math scores. So I’ll include them. Here’s third grade, African American.

Here, Lewis Lemon was scoring better than blacks in the district and state before the DI implementation. The blue still shifts right, but it’s not as dramatic. In 2003, virtually every student met or exceeded expectations, but in every other year, both before and after the DI implementation, they were still doing very well.

Now white 3rd grade math:

So in 2002 through 2003, the school saw a good bunch of whites move from “meets” to “exceeds”. Unlike reading, third grade white performance saw a decent boost, but it started a year earlier. Whites at Lewis Lemon performed better than the district.

And now, the fifth grade. Reading, black fifth graders:

Scores actually declined in 2003. 2005, the year that the third graders from 2003 were in fifth grade, sees a slight improvement. But not much of one–more than half failed to meet standards.

Fifth grade whites, reading:

Again, whites have their best year in 2002, and don’t show any particular spike. They also do better than black fifth graders (which is normal).

Again, whites have their best year in 2002, and don’t show any particular spike. They also do better than black fifth graders (which is normal).

Fifth grade math:

Indifferent–except note the spike when the third graders of 2003 show up. It’s much more pronounced in math than it was in reading.

White fifth graders, to finish out.

So here’s one last way of looking at the data–compares blacks at Lewis Lemon to the whites at the school, district, and state level. Read down on the left for 3rd and 5th reading, down on the right for 3rd and 5th math.

Once again a consistent pattern for black third graders–big boost in 2003, slight fade in 2004, then tank. Black fifth graders see the boost exclusively in 2005, when the rock star 3rd grade class arrives, holding on to their gains more so for math than for reading. Spike or not, black third graders at Lewis Lemon do well in math compared to district whites from 2002-2005.

And here are the formal demographics reflecting the disappearance of white students from Lewis Lemon.

That’s a stark drop in a short time. 47% or so from 2001 to 2003, and 50% from 2003-2005. It may have just been a drop in new students, but the third grade and fifth grade classes ran out of whites at the same time–I’d have expected the fifth grade cohort to have more white students for longer, in that case.

So restating the observations:

- Lewis Lemon black 3rd grade scores are stupendously high in 2003. The accusations of cheating were groundless, unless the cheaters carefully waited two years to boost the same kids’ scores when they hit fifth grade.

- However, black 3rd grade scores at Lewis Lemon were consistently higher than black scores district and state wide, before and after the program.

- White students saw no real benefit from the new program.

- Fifth graders, white or black, saw no real benefit from the program. The one strong category, fifth graders in 2005, is the boost of the third graders from 2003.

Questions:

- Is it possible that the 3rd grade class of 2003 was in some way extraordinary?

- Were the white and black 3rd grade students practically (that is, for some legal reason) separated? Did the black students have a different teacher than the white students?

- Did the white flight remove more high ability students? But even if it did, you’d expect the white kids to respond as well to DI as black kids,

- Could parents “opt out” of DI?

- Was the white flight out of Lewis Lemon exacerbated by the switch to DI? White students did not see the dramatic increases. Maybe they didn’t like the new regime?

Conclusions:

Well, it’d need a better analyst than me to evaluate the data. And if there’d been solid analysis and reporting at the time, we might have a better idea why the black third graders did so well. Clearly, the curriculum is a possibility for the higher reading and math scores. But I can’t explain why subsequent third grade classes fell off in performance. And I really can’t figure why the white kids didn’t do well, unless it’s for the same reason that white kids don’t do KIPP.

Did the meta-analysis include Lewis Lemon?

What I don’t see is a miracle. What I don’t see is conclusive test evidence showing an obvious incremental increase in test scores at every level, in every demographic, or in every race. Given the actual, honest to god data, not a compiled version of it, broken down by both race and grade and score category, is easily available, I hope someone can go even deeper into the data and see if they find explanations or patterns that aren’t available in this surface level display of data.

Here’s what else I don’t see: any reason whatsoever for that domineering control freak superintendent to rip the program out of Lewis Lemon. I’m not a fan of D, but reading about this blatant obliteration of something that worked for the kids has been depressing. Shame on the media for not digging deep at the time and finding out why.

So there you go. Real data on Direct Instruction. Have at it. Draw your own conclusions.

Happy New Year.

‘

‘

Notice that white high schoolers and high school graduates have roughly the same scores as blacks with 4 year degrees or more. This is a very consistent finding in most test score data.

Notice that white high schoolers and high school graduates have roughly the same scores as blacks with 4 year degrees or more. This is a very consistent finding in most test score data.