Bless me Father for I have sinned. It’s been four and a half years since my last curriculum article.

My entire teaching career has been spent navigating a student ability gap that got noticeably wider sometime before the pandemic. The strongest kids are getting better, the weaker ones spent middle school not learning a thing because they’d pass anyway. (Thank you, Common Core.)

I am constitutionally incapable of giving an F to kids who show up and work. Call it a failing if you must. So yes, the gap grew, but I adjusted and got back to moving the unengaged kids forward, building the confidence of the kids willing to play along, and pushing the top kids as far possible, given the ability ranges.

But tests were increasingly a problem. My long-standing approach was to allow all students extra time to finish tests or ask questions. But this was premised on a much smaller gap and by this time the gap is a canyon. Add to that the fact that cheating is just an enormous issue post-pandemic, so giving kids access to the tests after school and at lunch increases the chance of them getting a camera on the questions, posting it on Discord, using photomath, memorizing the question to ask a classmate, whatever. Once upon a time, kids were just grateful to have the chance for extra time, but lo, those were the days of yore. So I want more kids finishing all or most of the test within a single class, and if they need extra time I want it wrapped up quickly.

To understand the nature of my dilemma: If I build a quiz that my weakest kids (10-20% of the class) can get a high F, D, or C after the entire class period and an hour of additional supported work, the top kids (30-40% of the class) will finish it in 10 minutes. I’ve given quizzes that the top kids are handing in before I’ve finished handing them out.

That’s just straightforward quizzes. How do you build a cumulative unit test that challenges your best kids that your weakest kids won’t flunk by giving up 20 points? Or takes them eight hours to work through and then flunk with 40 points? How do you make something manageable for your strugglers that isn’t a five minute exercise for your strongest students?

The idea hit me in November when I was building the unit two test. I’d pulled up last year’s version. It was a good test, but the strongest kids had finished it in 40 minutes, and the weakest students from that class were far better than my 30 weakest students (out of 150) from this year. So I’d be giving a test that the best kids would blitz through, the middle kids would struggle with, and the weakest kids would give up and start randomly bubbling.

As mentioned, I’ve got just the one prep. So instead of this two or three weak students, 10-12 strong students, it’s 40 weak students, 60 strong ones, and 40 midrange.

Never mind the aggravation, it’s just crap, pedagogically speaking. My weaker students need math they can do, build up their confidence. My strong kids need…doubt. Challenge. Something more than the straightforward questions that strugglers need.

Suddenly a familiar thought snuck in: I could create two tests. Not two different versions of the same test. Two tests of entirely different questions on the same topics, one much less challenging than the other.

Familiar because I’ve wanted to do this …well, since before the pandemic, at least five years ago, when I first accepted that the gap wasn’t getting any better. But every other time I dismissed the notion. I usually teach from five to seven different classes a year, so that would be 10 to 14 tests, some of which would only be taken by five or six students. Not worth it.

But hey. I’ve got just the one prep.

Maybe I could make a little lemonade.

Requirements:

- The tests had to have the same number of questions, the same answer choices, tests the same topics. I build my own scan sheets and I wanted to be able to make each test a different version on the same scantron.

- Questions had to be on the same topic. I organize my tests by section, with each section having from 4 to 6 questions. The situations presented in each test had to be on the same general topic, and the questions asked had to explore the same knowledge base.

- My weak students couldn’t get As or Bs on their tests. I couldn’t say “an A on this test is really a C”. The easy test had to be hard enough for my weak students to get a C or B- at best. I wouldn’t have even considered taking this on without confidence in my test development skills, but admitting failure had to be on the table

- I had to be accurately categorizing students. The “easy test” scores had to be overwhelmingly C or lower with only a few outliers doing well, and no As. The “hard test” could have more variance, as I already suspected some degree of cheating at the high end of my class, but well north of half the students needed to come out of the first test with an 85% of higher. If I met this objective, then I’d decide what to do with the kids who scored too high or too low. But if I had too many students flunking the hard test or acing the easy test, then my whole theory of action was flawed and I had to give up on the idea.

So I made two tests–well, technically, two tests with three versions. Two versions of a challenging test, one I thought would really push the median B student in my class. One version of a test that I thought would be manageable but tough for the strugglers.

About a hundred students got the hard tests; forty something got the easy test.

Results of the first scan:

- Half of the “hard test” students got an A. Another 10% got a high B, which I counted as an A (this was a tough test). Another 10% got between 75 and 85%, indicating they knew what they were doing and just had a few fixes. The rest tanked badly, scores of 30-60%. More false positives than I expected, but enlightening. These students clearly knew more than my strugglers but there was a clear ability line separating them from the top students. I had a bigger middle than I knew.

- All but two of the weak kids got above 50% on the easy test (two didn’t finish), but only three got 80%, and about 10 got above 70.

I was accurately categorizing students. Well enough at least to continue. And I have, since then, on both tests and quizzes.

The “middle” students needed a mama bear test, and I built a new one that did the job. From that point on I always created three tests, which allows me more flexibility in moving students around. I only build two quizzes (again, I’m talking about difficulty levels; I still build multiple versions of each quiz to cut down on cheating). About 60 kids take the hard test, 40 taking the middle and 40 taking the easy version.

I’m extremely pleased with the results. First, my top kids love the harder tests. A number of students who just thought they were top kids got a dose of humility and started paying more attention. I’ve made math harder for them in, I think, a positive way. They can’t complain that I’m being unreasonable when a fourth of the students are acing the harder tests.

But the real impact has been on my strugglers, who range in motivation from absolutely none to never stops plugging away. They work harder on the tests and quizzes instead of just giving up. They work more in class, finally seeing a link between their effort and achievement. While they all still have difficulty on unit tests and integrating their knowledge, their quiz scores have seen considerable boosts. I’ve actually been able to make the “easy” quizzes more difficult and still see high passage rates.

Regular readers will note a recurring theme of mine: My weaker students are learning more not because I raised standards, but because I lowered them.

Allow me to quote the degenerate wise man, Joe Gideon, once more: Listen. I can’t make you a great dancer. I don’t even know if I can make you a good dancer. But, if you keep trying and don’t quit, I know I can make you a better dancer.

Rigor and high expectations are, forgive me, not the way to make kids better students.

Anyway. It’s working. My weak kids are doing better and my top kids are getting stretched. Score a single lonely point for giving me just one prep.

********************************************************************************

Some notes:

Back in 2015, I wrote a lot about my “multiple answer math tests“, as I called them–inaccurately. I still use them, updated them to a scan sheet. Given how essential and permanent these tests are in my work,it’s odd I haven’t written about the format since. To understand this post, you may want to read about the test structure, which is somewhat unusual, I think. I’ve changed the format somewhat since then, with less T/F, but the organization of multiple broad topics with many questions per topic is the same.

While students get the same points for questions, I weight some free response questions with more points on the harder tests. Not always, but sometimes the questions are in entirely different orbits of difficulty. Still, I keep an eye out for students who are getting all the questions right on the easier tests, as it’s a sign they need to move up.

Students have moved up and down. Three or four strong students were coasting off of the easier tests and like their phones way too much. Some figured this out and got serious, others didn’t. Some students have moved permanently from the low test to the mid-range test.

Ever since I found my test on Discord last year I’ve quit returning tests, which makes all this much easier. The top students have realized there are different tests beyond just versions, but after a few questions early on they quit mentioning it. They all seem to like it.

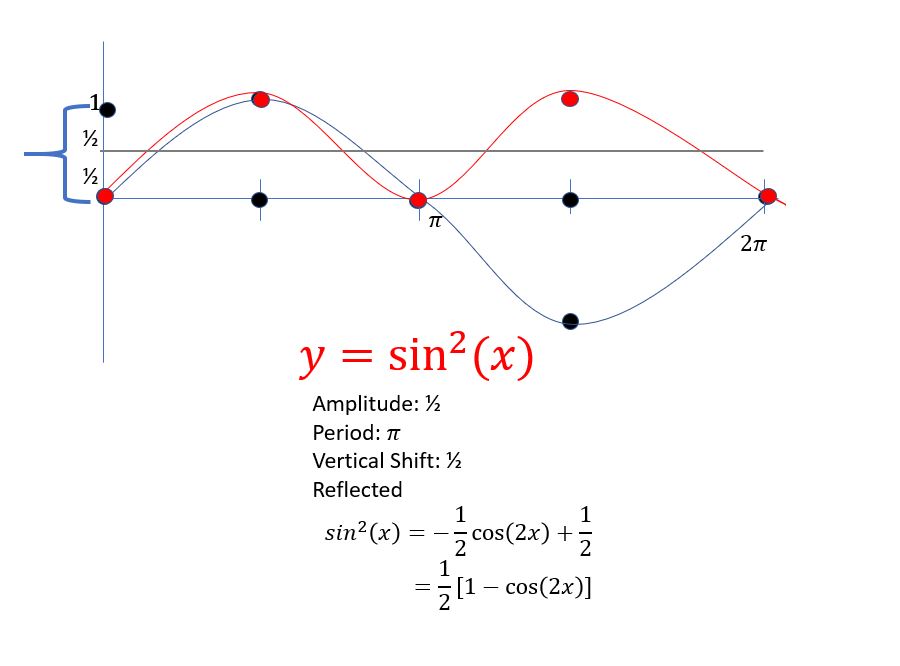

I almost gave up on this post twice because I couldn’t figure out how to display images of the different difficulty levels on the page. Here are some examples:

Or, as he says in the memoir, “Life educates.”

Or, as he says in the memoir, “Life educates.”