(with apologies to Rick Hess, who means exactly the opposite of me when he says it.)

Matt Yglesias is a liberal I’ve followed for years. He’s become more temperate since his signing the Harper’s letter, now that he’s realized how insane the progressive left has become. But if you want a representative sample of why Democrats turned away from neoliberalism, Yglesias is your guy. In his recent two part article that’s ostensibly about critical race theory, he rehashes the nostrums he’s been pushing his entire pundit life. Naturally, Twitter moderates were ecstatic.

If I wrote an angry takedown every time an ed reformer preached nonsense–well, I’d write more, so maybe I should. But Yglesias, despite making a few concessions I was happy to see, shocked me with his implicit….lies? misrepresentations?…ignorance? not sure which.

I really, really wish that people with megaphones could be reasonable about unions. It’s fine to hate them. It’s stupid to think they have much in the way of influence. It’s worse to pretend that education reform proposals failed because teacher unions prevent them. Most egregious of all is to pretend that charter school expansion and merit pay for teachers hasn’t been tried and rejected.

But this is just normal, ordinary middlebrow pabulum. This passage is shocking in its naivete, ignorance, or dishonest–take your pick.

I mean, my god. We have not yet been able to persuasively demonstrate through test scores that particulates, healthy meals, or even air conditioning in the summer has any impact on student achievement, particularly not at a granular level. We’ve spent billions on free lunch programs and air conditioning and a host of other environmental adjustments. The achievement gap endures. Thestudents tossed the healthy food in the trash.

As for standardized tests, surely the past thirty years of debate should have informed him that no, everyone does NOT agree that we can assess competence with a test. Why else are colleges so insistent on committing affirmative action? Why did so many of them seize the opportunity of the George Floyd moment of righteousness to use GPAs instead of SAT/ACT scores? Why are so many black activists angry about the “achievement gap”? A significant chunk of the institutional left believes those scores are lies–or at least unpleasant ephemera that can safely be ignored.

Most egregious: Measuring teacher impact via student achievement “would be uncontroversial”? Doesn’t this sound like he thinks VAM would be this terrific, obvious improvement if only policy makers could stand up to unions and put this sucker in place?

The Obama administration wasn’t just “open” to value add–it mandated some form of student performance metrics to any state trying to qualify for Race to the Top funding. Forty three states complied with a strict form of value add by 2014. Twenty three states mandated student performance metrics for teacher tenure decisions. Teachers unions sued endlessly to stop these mandates, and lost, time and again. (Once more, with feeling: unions have no influence on their own. They win when a major player agrees with them: districts, parents, or politicians.)

The entire rationale for VAM was first popularized in “The Widget Effect“, an article that argued for more differentiation in teacher evaluations, since 99% of teachers got a good review. But data revealed that three years of VAM resulted in….99% of teachers getting a good review. When states didn’t water down the test component, principals simply juked the stats.

Research isn’t the conclusive slam dunk that Yglesias’s “uncontroversial” implies, either:

- RAND: VAM are not absolute indicators of teacher effectiveness and are imprecise.

American Statistical Association: VAM measures correlation not causation, can change substantially based on model used, and show that teachers affect from 1-14% of variability in student test scores. - For a complete review, pro and con, of the research, Scott Alexander does his typical deep dive into VAM and finds it wanting, as does the great (and MIA) Spotted Toad.

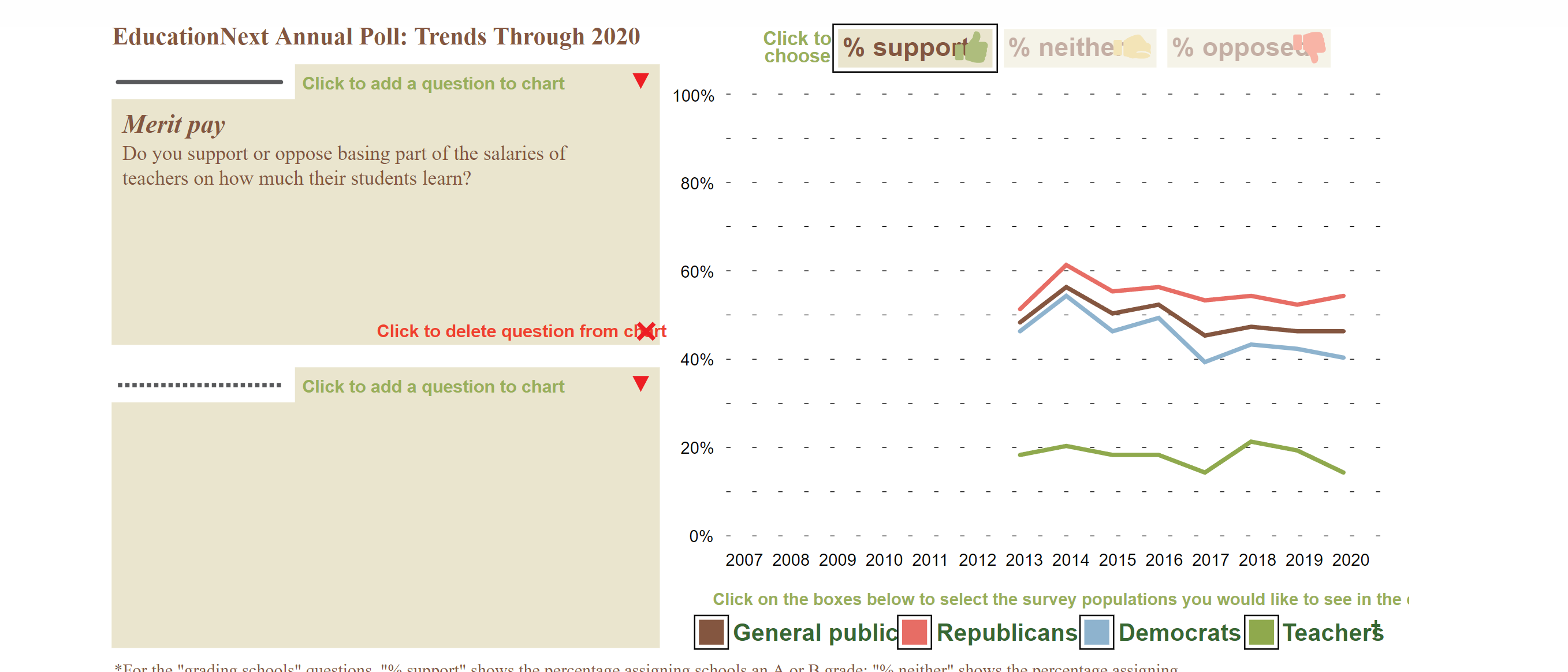

By 2016 ESSA, the most recent version of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, had removed all the evaluation mandates. Twenty three states no longer required VAM in evaluations, another fifteen did but left it up to districts to determine implementation. Public opinion, always split, declined:

New Mexico, the one state that genuinely gave bad reviews and fired teachers for insufficient value-add, unwound the entire program with a new administration that explicitly promised to undo the policies wrought by the previous governor Susanna Martinez and her reform darling ed chief, Hanna Skandera.

Yglesias’s representation of VAM as an uncontroversial implementation blocked by only by those unreasonable unions, is absurd. States, desperate for federal funding, implemented a wide range of value-added metrics that infuriated teachers. Public approval dropped, principals show by behavior they didn’t agree with the results, and research is at best equivocal.

Yglesias’s casual offhand shilling for charters is at least anodyne, if not original. But a close read reveals an interesting bias. While conservative education reformers emphasize parent choice, read closely and it’s clear Matt would cheerfully override parents and voters if they don’t agree with him.

Shot #1:

Chaser #1:

So school closures were horrible, “real anger” was unleashed–but only by white parents. Meanwhile, black (and Hispanic and Asian) parents were, er, “less annoyed” (translated: while as many as 3 in 4 white parents wanted schools open, 1 in 2 or fewer non-whites preferred remote education, findings that have been consistent throughout the pandemic). Yglesias is saying, explicitly, that we should not give parents a choice. (That said, he at least acknowledged the racial difference in preferences, which almost no one else mentions, so props for that.)

Shot and Chaser #2:

Democrats have responded to their voters’ preferences by moving away from charters. Voters have rejected charters (he doesn’t mention that California, another previously strong charter state, has flipped a law that banned districts from considering the financial impact of charters–and this is after charter growth in California and the nation had stalled. These are all deep blue states, previously supportive of charters. Yglesias doesn’t have much interest in voter opinion–unless, of course, it agrees with his.

This is all chaser

Everyone who pushes for mayoral control of schools is arguing against voter control. All those school board recalls? Yglesias thinks they’re a bad idea–or at least, they’re a bad idea where non-white and poor parents might make decisions he doesn’t liike. Fine for the angry white parents in Loudon to recall their school board, but where it really matters, where achievement is low, let’s put school control in the hands of an executive. Once again, all this choice is fine unless Yglesias thinks he knows better.

The money quote that everyone’s been retweeting about nearly made my head explode.

Oh, hey, integration, choice, curriculum, merit pay, healthy food and higher teacher standards!! Damn. Here we could have knocked out decades of achievement gaps if we’d just known about these obvious policy changes and put them into action.

Oh,wait, we did. We tried. They failed. Achievement gap has been stable for years. NAEP scores stalled and then dropped after 20 years of the reformers running the table. And the kids dumped the healthy food in the trash. What now?

More money won’t help. School choice won’t help. Firing teachers won’t help.

Maybe education policy should start by realizing schools are doing a pretty good job, given the idiotic constraints imposed on them by people who don’t understand the limits of education. Maybe we should change some laws, drop others, and ensure we spend money on our neediest citizens (ask yourself how much Title I funding is going to Afghani refugees and border asylum claimants?). None of these failures mean that teachers don’t matter or that we can’t improve schools. But we have to understand what “improvement’ means. Most of the people screaming for better schools won’t approve.

I try not to be depressed by the regular evidence that the vast majority of people with megaphones don’t understand education. But it really was horrifying how many people approved of Yglesias’s recipe for improving schools, how few of them seem to understand what has already been tried and failed or tried and rejected dozens of times in the past fifty years. And hell, I needed something to write about. I’m stalled on three other pieces.

But in the interest of comity:

This, finally, is correct.

Note: I’ve written two articles on Value Add, one of which goes through the obvious logical failings, the other outlining the voter political rejection mentioned here.

Also, I don’t spend enough time praising Freddie deBoer, who is writing fantastic reality about education from the left. He might be a socialist or a Marxist or whatever, but he’s much more of a realist than anyone with a similar audience and mainstream politics. I particularly liked his article on college admissions (which led to one of the pieces I’m stuck on) and on resisting blank slate thinking.

Just a reminder that when I’m trying to write something, I do the second draft instead of the tenth to get anything out at all.