When the bell rings at Wheaton North High School, a river of white students flows into Advanced Placement classrooms. A trickle of brown and black students joins them. —The Challenge of Creating Schools That Work for Everybody, Catherine Gewertz

Gewertz’s piece is one of a million or so outlining the earnest efforts of suburban schools to increase their black and Hispanic student representation in AP classes. And indeed, these efforts are real and neverending. I have been in two separate schools that have been mandated in no uncertain terms to get numbers up.

But the data does not suggest overrepresentation. I’m going to focus on African American representation for a few reasons. Until recently, the College Board split up Hispanic scores into three categories, none of them useful, and it’s a real hassle to combine them. Moreover, the Hispanic category has an ace in the hole known as the Spanish Language test. Whenever you see someone boasting of great Hispanic AP scores, ask how well they did in non-language courses. (Foreign language study has largely disappeared as a competitive endeavor in the US. It’s just a way for Hispanic students to get one good test score, and Chinese students to add one to their arsenal.)

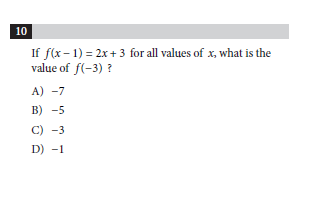

College Board data goes back twenty years, so I built a simple table:

I eliminated foreign language tests and those that didn’t exist back in 1997. It’s pretty obvious from the table that the mean scores for each test have declined in almost every case:

Enter a caption

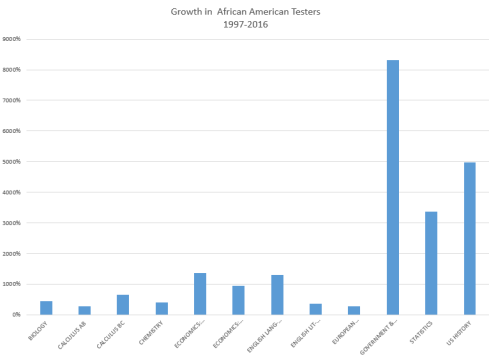

While the population for each test has increased, it’s been lopsided.

It’s not hard to see the pattern behind the increases. The high-growth courses are one-offs with no prerequisites. It’s hard to convince kids to take these courses year after year–even harder to convince suburban teachers to lower their standards for that long. So put the kids in US History, Government–hey, it’s short, too!– and Statistics, which technically requires Algebra II, but not really.

The next three show data that isn’t often compiled for witnesses. I’m not good at presenting data, so there might be better means of presenting this. But the message is clear enough.

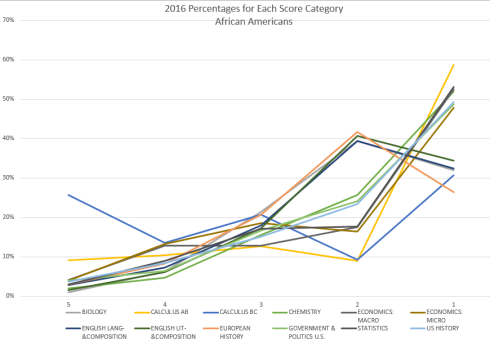

First, here’s the breakdown behind the test growth. I took the growth in each score category (5 high, 1 low) and determined its percentage of the overall growth.

See all that blue? Most of the growth has been taken up by students getting the lowest possible score. Across the academic test spectrum, black student growth in 5s and 4s is anemic compared to the robust explosion of failing 1s and 2s. Unsurprisingly, the tests that require a two to three year commitment have the best performace. Calc AB has real growth in high scores–but, alas, even bigger growth in low scores. Calc BC is the strongest performance. English Lang & Comp has something approaching a normal distribution of scores, even.

Here you can see the total scores by test and category. Calc BC and European History, two of the tests with the smallest growth, have the best distributions. Only four tests have the most scores in the 1 category; most have 2 as their modal score.

The same chart in 2016 is pretty brutally slanted. Eight tests now fail most students with a one, just four have a two. Worst is the dramatic drop in threes. In 1997, test percentages with 3 scores ranged from 10-38%. In 2016, they range from 10-20%. Meanwhile, the 4s and 5s are all well below 10%, with the cheery exception of Calculus BC.

Jay Mathews’ relentless and generally harmful push of Advanced Placement has been going strong since the 80s, even if the Challenge Index only began in 1998. So 1997’s result include a decade of “AP push”. But the last 20 years have been even worse, as Jay, Newsweek, and the Washington Post all hawked the Index as a quality signifier: America’s Best High Schools! Suddenly, low-achieving, high-minority students had a way to bring some pride to their schools–just put their kids in AP classes.

As I wrote a couple years ago, this effort wasn’t evenly distributed. High achieving, diverse suburban high schools couldn’t just dump uninterested, low-achieving students (of any race) into a class filled with actually qualified students (of any race). Low achieving schools, on the other hand, had nothing to lose. Just dub a class “Advanced Placement” and put some kids in it. Most states cover AP costs, often using federal Title I dollars, so it’s a cheap way to get some air time.

African American AP test scores don’t represent a homogeneous population, and you can see that in the numbers. Black students genuinely committed to academic achievement in a school with equally committed peers and qualified teachers are probably best reflected in the Calculus BC scores, as BC requires about four years of successful math. Black students dumped in APUSH and AP Government are the recourse of diverse suburban schools not rich enough to ignore bureaucratic pressure to up their AP diversity. They are taking promising students with low motivation and putting them in AP classes. This annoys the hell out of the parents and kids who genuinely want the rigorous course, and quite often angers the “promising” students, who are known to fail the class and refuse to take the test. The explosion of 1s across the board comes from the low-achieving urban schools who want to make the Challenge Index and don’t have any need to keep the standards high.

Remember each test costs $85 and test fees are waived by taxpayers for students who can’t afford them. Consider all the students being forced, in many cases, to take classes they have no interest in. Those smaller increases in passing scores are purchased with considerable wasted time and taxpayer expense.

But none of this should be news. Let’s talk about the real challenge of black students and AP scores and methods to fix the abuses.

First, schools and students should be actively restricted from using the AP grade “boost” for fraudulent purposes. The grades should be linked to the test scores without exception. Students who receive 4s and 5s get an A, even if the teacher wants to give a B1. Students who get a 3 receive a B, even if the teacher wants to give an A2 . Students who get a 2 receive a C. Students who get a 1 or who don’t take the test get a D–which, remember, will be bumped to a C for GPA purposes. This sort of grade link, first suggested by Saul Geiser (although I’ve extended it to the actual high school grade) would dramatically reduce abuse not only by predominantly minority schools, but also by all students gaming the AP system to get inflated GPAs. That should reduce a lot of the blue in this picture:

Then we should ask a simple question: how can we bump those yellows to greys? That is, how can we get the students who demonstrated enough competence to score a 2 on the AP test to get enough motivation and learning to score a 3?

I’ve worked in test prep for years with underachieving blacks and Hispanics, and now teaching a lot of the kids not strong enough or not motivated enough to take AP classes. My school is under a great deal of pressure to get more low income, under-represented minorities in these classes as well (and my school administration is entirely non-white, as a data point). A couple years ago, I taught a US History course that resulted in four kids being “tagged” for an advanced placement class the next year–that is, they did so well in my class, having previously shown no talent or motivation, that they were put in AP Government the next year. I kept in touch with one, who got an A in the class and passed the test.

My advice to my own principal, which I would repeat to the principal in Gewertz’s piece, is to create a class full of the promising but unmotivated students, separate from the motivated students. Give them a teacher who will be rigorous but low key, who won’t give much homework, who will focus on skill improvement in class. (ahem. I’m raising my hand.) Focus on getting the kids to pass the test. If they pass, they will get a guaranteed B in the class, which will count as an A for GPA purposes. (Even if the College Board doesn’t change the rules, schools can guarantee this policy.)

This strategy would work for advanced placement classes in English, history, government, probably economics. It could work for statistics. Getting unmotivated kids to pass AP Calculus may be more difficult, as it would involve using the strategy consistently for 3 years with no test to guarantee a grade.

The challenge of increasing the abilities and college-readiness of promising but not strongly motivated students (of any race) lies in understanding their motives. Teachers need to give their first loyalty to the students, not the content. Traditional AP teachers are reluctant to do this, and I don’t think they should be required to change. But traditional AP teachers are, perhaps, not the best teachers for this endeavor.

In order for this proposal to get any serious attention, however, reporters would have to stop pretending that talented black students aren’t taking AP courses. The data simply doesn’t support that charge. We are putting too many black students into AP courses. Too many of them are completely unfit, have remedial level skills that high schools aren’t allowed to address. Much of the growth of Advanced Placement has relied on this fraud–and again, not just for black students.

It’s what we do with the kids in the middle, the skeptics, the uncertain ones, the ones who dearly want to be proven wrong about their own skills, that will help us improve these dismal statistics.

1I can’t even begin to tell you how many teachers in suburban districts do this.

2The same teachers who give students with 4s and 5s Bs are also prone to giving As to kids who got 3s. But of course, this is also the habit of teachers in low achieving urban districts. Consider this 2006 story celebrating the first two kids ever to pass the AP English test, and wonder how many of the students got As notwithstanding.