I originally planned on following up on my group projects assignment within a week, but got distracted by semantics. I’ll probably put that in another piece some day.

Like many people, I conflate the terms “group work” and “group projects” in discussions. But they are totally different activities.

“Group work” in the educational world refers to a pedagogic strategy in which small groups (3-4 kids) are given the same task to complete. The tasks themselves are often designed to be open-ended. It’s part of the “collaborative learning” theory, explicitly designed for heterogeneous (untracked) classrooms. (I wrote about group work and collaborative learning a while back.) When people gripe about “expecting the smart kids to teach everyone else” in the context of group work, they are usually wrong. Teachers using collaborative learning often rebuke the kids who come up with “the answer” as opposed to allowing “everyone to contribute”.

“Group projects” have occasioned whining for decades longer than group work. But they can be a legitimate academic device to help students acquire certain skills. For example, students need presentation experience, but thirty individual presentations is torture to experience, never mind grade. Other times there just aren’t thirty topics to assign in depth. “Explore key events leading up to the Civil War” or “key playwrights in the Elizabethan era”. So for many reasons, group projects are educationally appropriate in certain cases. (Never in math, though. Unless you’re teaching a homogenous class of overachievers and have some spare time. hahahahaha.)

And yeah, group projects also prepare you for real life. Sure, one person might do the work while others get the credit. But slacker team members aren’t the only obstacle. Obsessive naggers, passive-aggressives, domineering fascists….all part of the interpersonal experience. Is it any wonder I spent life as a self-employed specialist and then went into teaching? Independent contributor, am I.

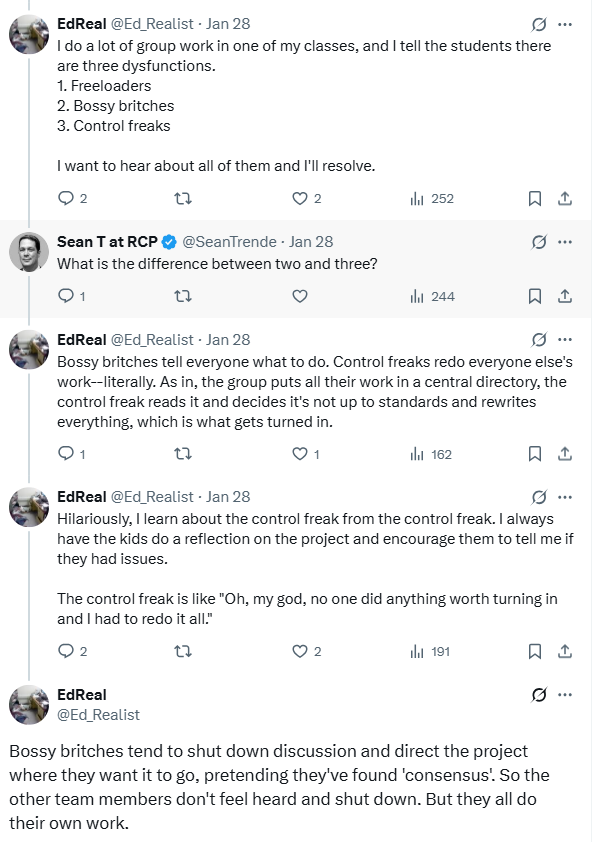

So how does a teacher assign meaningful group projects while maximizing the possibility of productive activity and minimize the impact of freeloaders, bossybritches, and control freaks?

My advice is to start by carefully considering group assignments.

- Most of the time, form groups by ability. This is important. It allows me to monitor the low achieving groups either to help them as they genuinely work or kick their asses if they slack off.

- Every so often, allow the kids to form their own groups BUT be up front that there will be no orphans. If there are kids who don’t have friends in the class, I generally put those kids together and then monitor them closely. Sometimes, I’ll have to add kids to an existing group and it helps to have made it clear up front that there will be no whining or exclusions.

- Also every so often, on carefully selected short-term projects, I do random group formation. Sometimes I use birthdays. But if I want to be sure the random groups are age or gender based, I feed the list to Grok or Claud and then review it (they often skip names or put someone twice in a group).

I always include a lecture up front. I expect to be informed of unhappiness. Ideally, ahead of time. If someone in on the phone constantly, I should notice and make that person unhappy. But if I don’t, tell me so I can proceed with the unhappiness. Hurt feelings, no one is listening to you? Tell me. . I may tell you to speak up more and stop sulking. I might also decide that you’ve got a steamroller who isn’t listening to anyone. Unhappy with your inferior teammates, having to do all their work again? Tell me. I’m going to order you to stop redoing everyone’s work and stop being such a damn control freak. I may also tell your teammates to step up and work harder.

And so on.

Most important of all: I always include a (forgive the ed word) reflection as part of the assignment. So the students turn in the group work as a collective effort, but each individual has to write a reflection. I grade the reflection as part of the project but it could be done independently as well. The reflection includes analysis of how the team worked together.

This not only gives me insight into any problems the team had, but also gives me a good idea of the relative participation of each member. It also allows me to modulate the grade so that slackers in particular get a lower grade. In fact, slackers often don’t turn in a reflection, which automatically drops their grade to a C.

A variation on this I’ve used when I’m suspicious that a lot of kids aren’t working is the “In Case I Get Hit By A Truck” assignment. I will suddenly announce in the middle of class to drop everything, pull out a piece of paper, and write down what has happened in the group thus far. Include diagrams, decisions, some flowcharts if needed. No talking. No consults. Just get it on paper.

Why? Because in the real world, your co-worker may suddenly disappear and your boss will expect you to take over. It’s….not fun. Don’t be that guy. And then, of course, I tell them that I never documented anything, so do what I say, not what I do.

Pedagogically speaking, an assignment like this early in the class will do much to discourage slackers. It’s also very useful to learn who needs to be watched carefully. Plus, they won’t get an A when someone else did all the work. Grade grubbers everywhere can rest easy, you obsessive competitive freaks. Kidding. Kind of.

Hey, under a thousand.